YOUR TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINTS

by John Bassett DDS

Our temporomandibular joints, or TMJs for short, are unique joints in the human body because not only do they hinge when we open and close our mouths, but they also slide forward and backward. We utilize this feature when we thrust our lower jaws forward to bite into something with our front teeth, as well as when we move out lowers law from side to side in order to chew. It is significant that when we open our mouths wide, the lower jaw both rotates and slides downward and forward. This movement can be felt by placing a finger directly in front of your ear while opening and closing your mouth.

These TMJs of ours are also unique in that they contain discs, which are stress absorbing pads made of cartilage-like material. We have discs in our knees and spine, but nowhere else. The discs in the spine and knee joints do not move, but just sit there like so many pads. Because the TMJs slide as previously described, the discs in the jaw joints are considerably more complex. They are attached to the inside and outside of the bony “condyles” (the knobs at the top of the mandible, which form the bottom half of the jaw joints,) much like a bucket handle. The discs are NOT attached to the top of the condyles. There are fluid-filled spaces above and below the discs. The fluid is held in by a fibrous capsule, which surrounds each joint.

The discs can become displaced anteriorly to the condyles, which is not normal. When this occurs as we open our mouths, the condyles slide forward, pushing against the back back of the discs. Often, the condyle slips under the thick posterior band of the disc into its normal position, and a clicking or popping sound is heard and felt. This is often painful, but not always. A corresponding click is usually perceived as the condyle slips out from under the disc during closure. When we are closed, the disc is now out of place, or “displaced.” An interesting diagnostic maneuver when one is in this condition is to open the mouth until it clicks, then close with the mandible advanced by biting on the front teeth. The clicking suddenly disappears because the condyles are not permitted to slide backward out from under their discs. As long as the mandible is held forward, no clicking occurs. This phenomenon is useful in treating this condition.

When the condition remains untreated, the repeated pushing forward by the condyles against the back of the discs forces the discs in their proper place. As the disc is pushed forward, the clicking sound occurs later and later in the opening movement (the mouth is wider open when the click occurs.) Eventually, the disc is so far out of place that it no longer clicks into its correct position and typically the patient notices that the joint “locks,” i.e., the mouth wont open as wide anymore. A simultaneous limitation of opening range and cessation of the clicking is diagnostic of this condition. We call this condition, “closed lock.”

There is considerable disagreement within the profession as to the cause of these conditions. Some doctors, especially academics, believe this is a psychological condition, and it is best treated with psychotherapeutic drugs and counseling. To us, this approach is ludicrous. Many TMD sufferers do indeed manifest psychological symptoms, but we feel that is mostly because they have gone from one practitioner to the next in search of answers and relief, and have become frustrated when they have failed to find either. It is our feeling that this is a mechanical problem, which is caused by trauma: either macro trauma, (a large amount of trauma over a short time span) such as occurs when one’s teeth do not properly come together, known as malocclusion. We believe that since these conditions are mechanical, and have a mechanical origin, they logically have a mechanical solution.

Patients suffering from these conditions have three possible choices. They can do nothing and live with the problem, and many people do. If the discomfort is minimal or non-existent, that is a reasonable choice. We can surgically enter the joint, either with an arthroscope (a wand with a camera and other instruments attached), which is minimally invasive, or with a scalpel, which is much more invasive but permits considerably greater access and allows a wider range of corrective procedures. These are the same choices one would have with an injured knee, for example. The third option is to attempt to NON-SURGICALLY manage the problem, which is what we offer here in our practice.

PHASE ONE TREATMENT

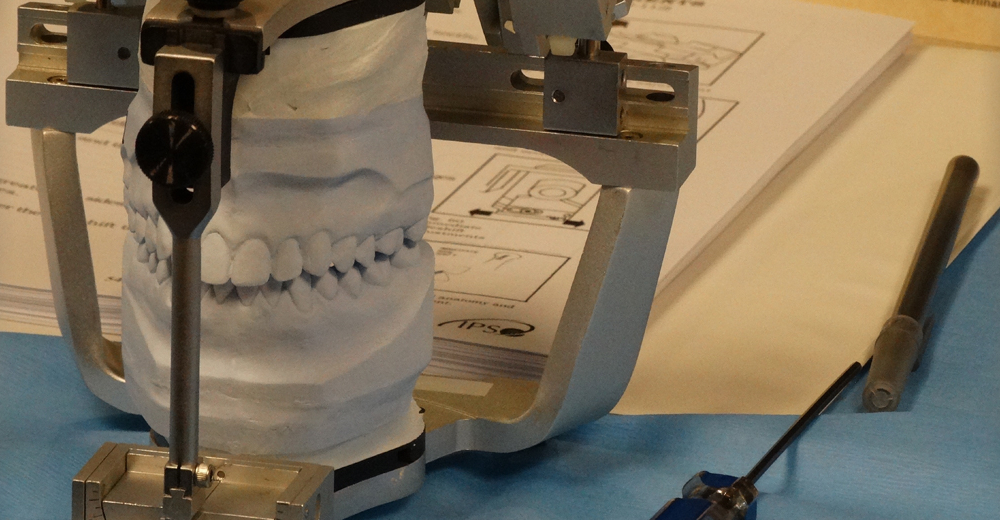

The non-surgical management of these disorders almost always involves the patient wearing an intra-oral appliance, or splint, in the mouth. The purpose of the splint is to utilize the very sensitive “proprioception,” or sense of touch, that the teeth possess in order to posture the mandible in a more desirable position for the structures in the joint. Without the splint, the manner in which the teeth interdigitate will determine mandibular posture; the splint provides a new bite and therefore a new joint position. In the case of a clicking joint, the jaw may be positioned “ahead of the click,” which we know is in its proper position under the disc. We call this splint an Anterior Repositioning Appliance, or ARA for short. If we leave the jaw in that position for a long enough time for the ligamentous attachments of the disc to heal, we can frequently achieve “recapture” of the previously displaced disc. It is our belief that if we can successfully pt the pieces back into their proper place, the attendant pain will quickly be relieved. Indeed, this is the usual result.

If, however, the patient we are treating is diagnosed with “closed lock,” the condition described above in which the disc no longer clicks, the simple act of opening the mouth does NOT cause the disc to pop back into its normal position. In this situation, we usually attempt to manually manipulate the disc into its correct position, and then hold it there with the same appliance just described (ARA), in order to allow it to heal. This manipulation is often painful, and is usually done by an oral surgeon with the patient under IV sedation. The ARA must be fabricated and in the mouth before the manipulation is attempted, or the disc will simply slip out of place again before the patient reaches the oral surgeon’s parking lot.

If the manipulation attempt is unsuccessful, the disc will then remain out of place. All, however, is not yet lost. Experience shows us that if we equalize the forces on all the teeth, we can minimize the stresses within the joint and often relieve the pain without actually capturing the displaced disc. We use a meticulously adjusted splint to accomplish this. Our percentage of success is not quite as high as if we put all the pieces in their proper place, but it is still well in excess of fifty percent, and certainly preferable to a surgical procedure. If, in spite of our best efforts, the patient continues to experience pain, the surgery is often indicated. Joint surgery, however, is a last resort and should always be accompanied by a splint, so most people are happy to attempt therapy beginning with only a splint, as the same appliance can be modified to be used in conjunction with joint surgery.

When the symptoms of the chewing system have been relieved by whatever means, be it splint, splint and manipulation, or splint and TMJ surgery, we consider that we have completed Phase One of treatment. The pain was eliminated months ago, normal function has returned, the joints are stable (unchanging), but the patient has to have this piece of plastic in his or her mouth 24/7 in order to be comfortable. We are now usually six to eight months into treatment. If we now remove the splint from the mouth and ask the patient to close together, the teeth do not fit at all well, because we have moved the lower jaw with respect to the upper jaw. If we did not continue with the appliance, the original symptoms would return, usually within a few months, and all our previous efforts would be lost. Our next task, therefore, is to eliminate the patient’s dependence upon the splint without having the symptoms return. This is what we can Phase Two treatment.

PHASE TWO TREATMENT

In order to eliminate the patient’s dependence upon the appliance, we MUST make permanent changes to the patient’s bit so that the occlusion WITHOUT the splint is that same as it is WITH the splint. In other words, when the splint is removed from the mouth, the teeth must hit EXACTLY THE SAME WAY as they did when the splint was in the mouth. There are only four ways we can accomplish this. We can meticulously reshape or recontour the teeth to make them fit together more ideally. When this is done properly and without mutilating the teeth, it is far and away the most conservative method at our disposal and, as such is our preference. We call this procedure occlusal equilibration. If, however, the bite discrepancy requires too much tooth alteration such that the teeth would be mutilated, other alternatives must be sought. Sometimes it is necessary to restore, or crown, several or all the teeth in order to achieve an ideal occlusion. This is rather invasive and usually quite costly to the patient, but may be appropriate in certain circumstances. Another option is to move the teeth to achieve an ideal an ideal occlusion, a procedure which is normally accomplished by an orthodontist using braces. This treatment will usually require at least one year to complete, and often longer. A fourth choice can be orthognathic surgery (surgery to straighten the jaws,) which may seem extreme, but could be the treatment of choice when a severe skeletal deformity exists. This choice is usually combined with orthodontics.

Regardless of which form Phase Two takes, we believe very strongly that some method of idealizing the bite must be undertaken so as to prevent the original symptoms from returning following Phase One treatment. If a patient is unwilling to participate in Phase Two treatment, there is no point in beginning with Phase One. Likewise, we believe it is irresponsible for a doctor to recommend a Phase Two treatment modality (equilibration, crowns, braces or orthognathic surgery) before Phase One treatment has been successfully completed.

This discussion is intended to educate the prospective TMJ patient as to the nature of the problem and is in some respects is an oversimplified. It is important to us, however, that our patients have a modicum of understanding as to the nature of their problem in order that they will be motivated to comply with our recommendations as we proceed through treatment. Should you have any questions about your condition or treatment, we would be happy to address them at any time. John W. Bassett, D.D.S.